Confessions of an imposter: is today the day I get found out?

Have you ever sat at your desk and looked around at your colleagues wishing you knew as much as them or were as talented as them? Have you sat in a meeting and found yourself wondering if you actually deserve to be there? Are you in a leadership position and spend your time worrying that your team, who are the real deal, might discover that you are in fact a phoney? Perhaps worst of all do you agonise over your boss discovering that you are actually incompetent and inadequate?

If you recognise any of these persecutory thoughts as your own dirty little secret, then it’s likely that you are suffering from the psychological phenomenon known as Imposter Syndrome.

The syndrome was first identified by psychologists Pauline Rose Clance and Suzanne Imes. In their 1978 paper, they theorised that women were uniquely affected by Impostor Syndrome. However, it is now acknowledged that it is not gender exclusive and is far more prevalent among a minority in any specific setting. For example, within a sector such as construction, where women are vastly underrepresented, it is especially likely for someone to feel like she got in by some fluke and doesn’t truly belong there.

An estimated 70% of people experience these impostor feelings at some point in their lives, according to a review article published in the International Journal of Behavioural Science. The idea that, contrary to the evidence, you’ve only succeeded due to luck and not because of your talent or qualifications can be crippling anxiety.

It is critically important that not all self-doubt is labelled as Imposter Syndrome. We are constantly learning, especially early in our careers, and you’re supposed to feel like you’re in over your head otherwise you’re probably not actually learning at all. That feeling of panic that someone might find out you don’t know something is valid if indeed you don’t. That is self-doubt and should be used positively to work harder and learn more.

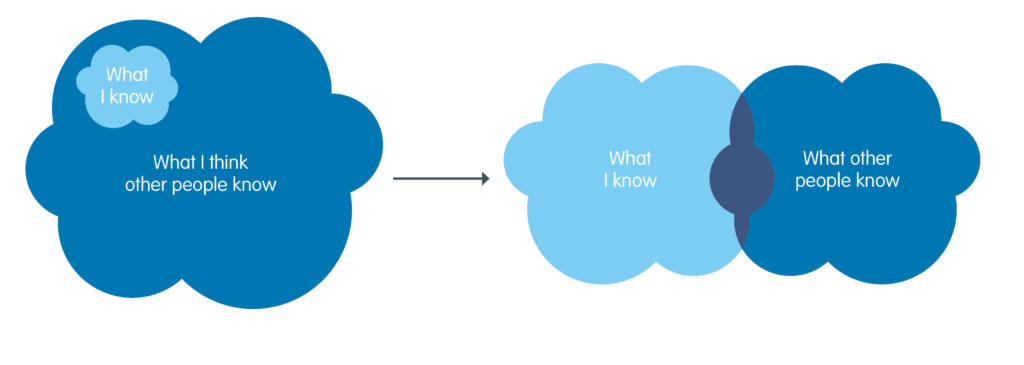

Without recognising this important distinction we risk misrepresenting the very process of learning and all that will do is push people towards the opposite end of the spectrum in a psychological phenomenon known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. This cognitive bias means the least competent people in a given area are far more likely to overestimate their ability compared to others. Ironically the converse is true for the most competent.

“The fundamental cause of trouble in the world today is that the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.”

Bertrand Russell

It’s important for individuals to recognise this internalised fear they are suffering is not entirely their fault – evolution is at least partly responsible. In a classic example of Darwin’s theory of evolution, it’s a survival of the fittest, meaning all humans live with degrees of anxiety, otherwise, Homo sapiens may well have died out long ago. The other generic human trait at play is, as children, our emotional need to belong often leads us to downplay our abilities as a survival strategy, believing it is better to fit in than stand out.

Imposter syndrome is not just an issue for individuals to be concerned about. For an employer, it can have a profound effect if left unchecked. The symptoms for individuals can be so severe that wellbeing can be dramatically affected by the increased probability of acute or chronic mental health issues. Also, in common with most mental issues, it can isolate individuals and negatively impact relationships. Finally, innovation can be stunted as chasing innovation naturally increases the risk of failure and, as such, sufferers are likely to shy away from innovation which would be self-fulfilling in terms of their fear of being ‘found out’.

So what can individuals and sufferers do to help? Self-doubt is a valid and important human trait which helps individuals come to a realistic assessment of their ability, competence and achievements. However, impostor syndrome is not a realistic self-assessment of inadequacy in specific situations, but a pervasive sense of unworthiness and inability. By definition, most people with impostor feelings suffer in silence, up against the constant fear they will be outed as a fraud.

To help identify as a sufferer of or someone suffering imposter syndrome Dr Valerie Young describes five types of ‘imposters’:

- The Expert: Those who will not feel satisfied in simply completing a task but must know everything about the subject. Continuously hunting for new information thus hindering them from completing a task.

- The Perfectionist: Those who are usually dissatisfied with their work, focusing on areas they could have done better rather than celebrating the things they did well. Often experiencing high levels of doubt and worry when inevitably falling short of their extreme goals.

- The Natural Genius: Those who are typically able to master a new skill quickly and easily but feel ashamed and weak when they cannot, therefore failing to recognise that everyone needs to work on their skillset throughout their life.

- The Soloist: Those who will typically decline offers of assistance so that they might prove their worth and prefer to work alone as requesting help will simply highlight their incompetence.

- The Superhero: Those who excel in most areas largely through pushing themselves so hard. Burnout from overload will often ensue, potentially resulting in physical and/or mental health issues and likely relationship issues.

Once ‘diagnosed’, there are some strategies which can be employed to help and all can and should be supported by the employer. Firstly, as with all mental health issues, there is a need to confront the symptoms by talking about them. This should help to distinguish between their perception and reality.

It is important to get educated about the syndrome and perhaps even try to identify with one of the five impostor personality types to help manage the specific symptoms and triggers. Challenging negative thoughts is a big part of trying to break the impostor cycle.

Line managers, assisted by a HR professional, can play a key role in helping and individual reframe their beliefs. Proper attribution is important so that sufferers can be helped to recognise when their hard work or skillset was fundamental to a specific achievement. Ensuring there is true inclusivity in the workplace is important, especially for minority groups, to ensure people feel the self-esteem that comes from a sense of belonging.

No one is perfect, so learning to accept one’s flaws and imperfections is essential to recognise your self-worth. The realisation that mistakes are not just inevitable but essential for learning and development. Don’t be foolishly overconfident but do embrace your self-doubt.